By Todd Schaller, WWA Vice President

By Todd Schaller, WWA Vice President

This article originally appeared in Wisconsin Waterfowl Association’s August, 2021 Newsletter edition.

Editor’s note: this article is Part IV in our series on exploring the issues surround a sustainable and ethical Sandhill Crane hunting season in Wisconsin. Part 1, Part II and Part III were published in earlier editions of our newsletter.

Since WWA started this educational series exploring the issues surrounding a sustainable and ethical Sandhill Crane (SHC) hunting season in Wisconsin, a point of discussion has been on the impacts SHC have on the agricultural community, and the partnership between agriculture and hunting.

Farming and hunting have a long partnership history on conservation topics which goes well beyond access to hunting land. Several federal and state programs benefit both agriculture and conservation: Wetland Reserve and Conservation Reserve Enhancement Programs (WREP and CRP), and Grassland Reserve Program to name a few. Also, it is important to appreciate that a significant part of waterfowl production occurs on private property – often agricultural land – especially in the prairie pothole region.

Farming and hunting have a long partnership history on conservation topics which goes well beyond access to hunting land. Several federal and state programs benefit both agriculture and conservation: Wetland Reserve and Conservation Reserve Enhancement Programs (WREP and CRP), and Grassland Reserve Program to name a few. Also, it is important to appreciate that a significant part of waterfowl production occurs on private property – often agricultural land – especially in the prairie pothole region.

In this article we’ll look more into the aspect of this partnership and Sandhill Crane crop damage. Like so many things on the surface it appears easy: SHC cause agricultural damage, maybe hunters can help reduce this damage. But it’s not that simple.

Sandhill Cranes are omnivores whose diets includes plants and animals. In simple terms they are generalists, eating plant tubers, grains, insects, mice, snakes. Basically, they eat whatever they find as they wander through their various habitats – wetland, upland, crop fields, etc. That said, like us, SHC have a list of preferred foods.

SHC frequently inhabit agricultural fields. Which makes sense since agricultural fields are often near emergent wetlands used for roosting and nesting. Take a drive around now and you’ll see families and groups of non-breeding cranes in recently harvested wheat fields.

When spring planting and SHC presence on those fields coincide, SHC can cause significant damage to newly planted crops. Conversely, cranes in a harvested field in fall are probably not a damage concern for a farmer.

A study by United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) showed a SHC can eat an average of 400 germinating kernels of corn per day in the spring, causing significant damage. In 2019, Wildlife Services in Wisconsin received 162 complaints regarding sandhill crane damage to crops, with reported damage estimated at $1.2 million. In most cases, the complaint numbers and damage estimates for a specific species (SHC) increase as the species population continues to grow. That certainly is the case with SHC.

So what tools are available to the farmer? Practical solutions to this spring planting damage include scare tactics, chemical treatment of seed and issuance of depredation permits (which are authorized by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act). While they may have some positive impact in addressing SHC-caused damage, they all require additional resources (time and money) by the farmer. In the end, these measures reduce, but do not eliminate, crop damage.

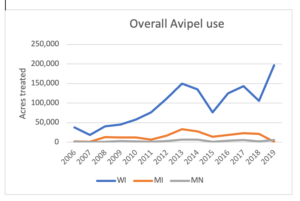

Chemical treatment of the seeds is done using a product called Avipel, which research has shown is an effective deterrent. Wisconsin agricultural use of Avipel is much higher than Minnesota and Michigan – and growing – probably reflective of relative damage levels. In 2019, about 195,000 acres of corn in Wisconsin were treated with Avipel.

Chemical treatment of the seeds is done using a product called Avipel, which research has shown is an effective deterrent. Wisconsin agricultural use of Avipel is much higher than Minnesota and Michigan – and growing – probably reflective of relative damage levels. In 2019, about 195,000 acres of corn in Wisconsin were treated with Avipel.

While fairly effective, use of Avipel increases production costs to the farmer (estimated at $10/acre), introduces another chemical into the ecosystem, requires additional steps in the farming operation and can impact the planting process and seeder machinery. Avipel also doesn’t prevent SHC from using planted fields; Avipel changes what they are eating in the field – treated seeds just don’t taste good to the birds. Cranes will still be in the agricultural field, but select other foods.

While Avipel is a broader approach to damage, USDA also authorizes depredation permits, a more focused approach to damage caused by SHC.

Depredation permits are issued after specific SHC damage is confirmed by USDA and non-lethal options have been tried and failed. While effective in removing SHC, depredation permits and scare tactics relocate the birds to another area, where they often continue to be a crop damage threat. Also, per the Migratory Bird Treating Act, any birds killed under a depredation permit must be destroyed, often buried or incinerated. Over the past few years, the number of SHC removed through depredation in Wisconsin is around 1,000 annually.

One challenging aspect of agricultural damage programs to manage SHC damage is cost and funding. Currently, SHC damage mitigation measures are completely funded by the USDA program. The DNR would assume some significant fiscal responsibilities if SHC would become a Wisconsin game species.

The DNR’s Wildlife Damage Abatement and Claims Program (WDACP) provides damage prevention assistance and partial compensation to farmers when wild deer, elk, bear, geese and turkeys damage their agricultural crops. The WDACP is funded through a $2 surcharge on each hunting license (deer, bear, small game, etc.), $4 on each Conservation Patron’s license, and revenue generated from the sale of antlerless deer carcass tags. Funding is pooled and then used for all program costs.

If SHC becomes a games species with an associated hunting season, damage costs would likely be included within the WDCAP program. A key question is what would be the additional costs of the program if Sandhill Cranes were added as game species, versus the available revenues.

To summarize:

- The partnership between the agriculture and hunting community will continue to be important in developing a SHC hunt in Wisconsin.

- Population management of species has been a component of historical strategies to mitigate agricultural damage, but,

- Current USFWS allowable (and actual) harvest levels across the flyway are not likely to have a significant impact on the Eastern Population of SHC.

- Growing populations of SHC will produce increasingly greater agricultural damage, mostly during the spring when a season is not currently contemplated by the USFWS regulations.

- Current Wisconsin depredation permits allow nearly 1,000 SHC/year to be killed and left in the fields.

- There will be financial impacts on the WDCAP program if SHC become a games species.

None of this information says a sustainable and ethical Sandhill Crane season isn’t practical or possible. It emphasizes what we’ve said from the being of this SHC series: understanding the range of interconnected issues and developing partnerships will be key to developing such a hunt.