This article originally appeared in Wisconsin Waterfowl Association’s June 2020 Open Water Newsletter edition.

I first met Peter Peshek in Madison about a year ago, after a duck stamp fee meeting in Madison with legislators, staffers, and other conservation groups. I had been in the executive director position a few months, and a mutual friend introduced us with the thought that Peter’s perspective and experience might prove beneficial in my new duties with WWA. Sitting down with Peter, we traded stories and histories (he served as DNR Secretary for a short period, amongst many other influential positions in and around Madison). Peter, is a lawyer by education and a scholar by nature, and I left impressed with his logic, knowledge and insights. I also left with a “homework assignment”! He tasked me to brush up on the history and scientific basis for the changed waterfowl migratory patterns seen in Lake Michigan over the past few decades—including a book and several articles—which were pretty helpful in understanding how this unusual hunting opportunity developed. But in turn, I’ve relished the opportunity to “task” Peter—to condense my homework assignment into a short article for you, the reader. I’m glad he accepted the assignment. — Bruce Ross

Bruce Ross has given me an impossible task. Peter, please write a short essay on the background of the creation of a Lake Michigan zone for duck hunting. In short, discuss forty years of regulatory modifications and the greatest change to the Lake Michigan eco-system since the retreat of the glaciers, all in about three hundred words. While I am a U.W. Madison History Major, Bruce wanted a non-scientist, non-regulator to write this background piece.

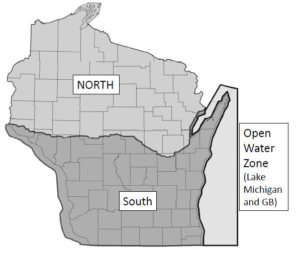

The history of creating duck hunting zones is the easy part. In 1991 the USFWS established guidelines for individual states. States were to create zones in order to “provide for a more equitable distribution of harvest opportunity for hunters throughout the state.” Wisconsin kept a two-zone strategy for twenty years with a “North” and “South” zone.

Meanwhile, man was making shambles of the Great Lakes ecosystem. The St. Lawrence Seaway opened in 1959 and that year marks the foundation for the Lake Michigan zone. In his Pulitzer Prize finalist 347-page book “The Death and Life of the Great Lakes“, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel writer, Dan Egan observes:

“Seaway ships have also been hauling something not listed on their manifests – noxious species from ports all over the world that are inexorably unstitching a delicate ecological web more than 10,000 years in the making.”

Egan’s book focuses on the impact these species had on fish. However, the invasion of Zebra and Quagga mussels (“which suck the plankton – the life – out of the water they invade”) were also having an equally profound impact on duck species on Lake Michigan. The explosion of mussel beds led to an equally profound explosion in diver ducks.

It was University of Wisconsin – Green Bay scientist Vicki Harris and her colleagues who recorded a major increase and, if you will, invasion of numerous diver duck populations in the Lake Michigan/Green Bay waters. The Long Tail duck became the poster child of these many hundreds of thousands of ducks. Pat Durkin summarized her research:

“Victoria Harris, a researcher who documented diving ducks’ growing presence in the 1990’s, wrote that their visits boomed 220% to 1.83 million duck-use days by fall 1997, primarily lesser scaup, greater scaup and goldeneyes. From 1994 to 1997 alone, scaup visits increased 128% despite only a 9% decrease in the species’ mid-continent population those years.”

Meanwhile, policy makers impacted the food base for ducks on the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers, among others. A registered nurse became known as “the clam lady” as she tried to protect the Higgens Eye Clam from commercial operations on the Mississippi River. Mussel beds disappeared on the Illinois River. Soon, Lake Michigan and Green Bay became the new home of Red Heads and other species who found the new exotic mussel beds a reliable food source.

By 2011, Wisconsin created a three-zone regiment adding the Mississippi River as a separate hunting area. There would be a twelve-day October split on the Mississippi.

The big water hunters of the east coast did not get a Lake Michigan zone in that, or the 2016 five year regulatory cycle, for two reasons. First, the Mississippi River guides, and their allies politically out-hustled the big water hunters. Secondly, the Green Bay hunters didn’t want the world to know just how incredible hunting had become over the last few decades.

Today, several things have changed, First, the twelve day split season on the Mississippi River lost support. The Mississippi zone and the South zone have nearly identical seasons. And, the world now knows how great open big water hunting is!

Next year, as Wisconsin looks forward to its first Lake Michigan zone hunt, the Natural Resources Board will have to define what the season will look like. It should be an interesting process.

Peter grew up on the east side of Two Rivers with the sand dunes of Point Beach State Forest as his playground. He was introduced to duck hunting by a DNR seasonal warden and a retired FWS warden while serving as head of the Wisconsin Department of Justice Criminal Protection Unit. He went on to serve as Wisconsin Public Intervenor. He is a self-taught big water hunter after he and his wife, Sharon brought a Door County cottage in 1975.